Six years ago, Microsoft officially unveiled Windows Phone 7 Series for the first time. It was the start of a journey that began with extraordinary optimism about the future of the company’s mobile efforts, despite the fact that it was launching late into a market that had already seen the arrival of two hugely capable, and fast-growing, competitors with fierce ambitions to dominate the smartphone space.

In the years that followed, Microsoft never managed to realize the potential of the first-generation product that it presented to the world on February 15, 2010 – indeed, such was the enthusiasm with which Windows Phone 7 was first received that many analysts predicted that it would go on to capture a significant chunk of global market share, even surpassing that of the iPhone.

Unfortunately, for Microsoft at least, the story of Windows Phone hasn’t been a particularly happy one so far.

In the beginning...

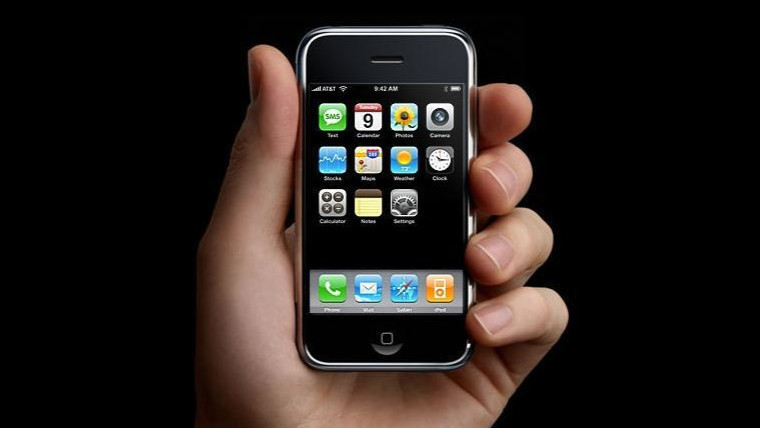

In January 2007, Apple unveiled the iPhone. It was ferociously expensive, lacked third-party app support and was limited to 2.5G speeds at a time when 3G devices were becoming increasingly affordable. Even some basic functionality available on other handsets was missing from iPhone OS, including support for copy-and-paste and MMS.

Nonetheless, even before it had gone on sale, many could see that the device represented a strong foundation for what was still to come, believing that with a few updates and refinements, the iPhone could be a big hit. Microsoft’s CEO at the time, Steve Ballmer, was not among them.

Speaking with USA Today in April 2007, Ballmer was asked: “People get passionate when Apple comes out with something new – the iPhone; of course, the iPod. Is that something that you’d want them to feel about Microsoft?” He replied:

It's sort of a funny question. Would I trade 96% of the market for 4% of the market? (Laughter.) I want to have products that appeal to everybody.

Now we'll get a chance to go through this again in phones and music players. There's no chance that the iPhone is going to get any significant market share. No chance. It's a $500 subsidized item. They may make a lot of money. But if you actually take a look at the 1.3 billion phones that get sold, I'd prefer to have our software in 60% or 70% or 80% of them, than I would to have 2% or 3%, which is what Apple might get.

In the case of music, Apple got out early. They were the first to really recognize that you couldn't just think about the device and all the pieces separately. Bravo. Credit that to Steve (Jobs) and Apple. They did a nice job.

Ballmer’s dismissal of the iPhone has since gone down as one of the greatest errors of judgement in tech history, and it wouldn’t be the last time that Microsoft’s hubris and complacency towards its rivals would leave the company with egg on its face.

Ballmer’s dismissal of the iPhone has since gone down as one of the greatest errors of judgement in tech history, and it wouldn’t be the last time that Microsoft’s hubris and complacency towards its rivals would leave the company with egg on its face.

At the time, Microsoft’s mobile efforts were based on its Windows Mobile 6 operating system, which could trace its roots back to the ancient Pocket PC, built on Windows CE foundations. While WM6 supported devices with touch-sensitive displays, the interface was far from ideal for touch inputs with fingers and thumbs; most such devices came with a stylus, and even those units that were supposedly optimized for true touch support – like the HTC Touch – relied on third-party UI overlays, rather than OS-level design considerations.

But even as its CEO dismissed its shiny new iPhone rival, behind closed doors, Microsoft knew that it would need to respond to the threat of that device. Unfortunately, it would not do so for another three years.

Photon

In 2007, Microsoft had already been working on a major update for Windows Mobile for some time, albeit still based on the Windows CE framework. Later referred to as ‘Windows Mobile 7’, it was developed internally under the codename ‘Photon’, and work had begun on the project sometime around 2004-5, with initial plans to launch by the end of 2007.

In 2007, Microsoft had already been working on a major update for Windows Mobile for some time, albeit still based on the Windows CE framework. Later referred to as ‘Windows Mobile 7’, it was developed internally under the codename ‘Photon’, and work had begun on the project sometime around 2004-5, with initial plans to launch by the end of 2007.

Leaked screenshots – including some that emerged much later, in 2010 – indicated that the UI was based to a considerable extent on what had come before. The interface drew heavily from that of Windows Mobile 6, but included many newer design elements borrowed – to varying degrees – from some of Microsoft’s other products, including Windows Media Center and the Zune media player.

But as development on Photon continued, its planned release date slipped several times. The longer the project wore on, the more Microsoft found itself attempting to rejuvenate an OS designed for a bygone era at a time when consumers were increasingly warming to the fresh and stylish proposition of the iPhone. Worse still, the company also faced a new threat to deal with when, in late 2007, the Open Handset Alliance, led by Google, unveiled the first version of Android with plans to launch devices running the OS from several manufacturers. Ballmer swiftly dismissed the threat of Android as "just some words on paper right now".

But as development on Photon continued, its planned release date slipped several times. The longer the project wore on, the more Microsoft found itself attempting to rejuvenate an OS designed for a bygone era at a time when consumers were increasingly warming to the fresh and stylish proposition of the iPhone. Worse still, the company also faced a new threat to deal with when, in late 2007, the Open Handset Alliance, led by Google, unveiled the first version of Android with plans to launch devices running the OS from several manufacturers. Ballmer swiftly dismissed the threat of Android as "just some words on paper right now".

By 2008 – when Apple had launched its second-generation, 3G-enabled iPhone; and the first Android handset, the HTC Dream, was on the horizon – Microsoft must surely have realized that its efforts to put new lipstick on its old pig were becoming increasingly irrelevant. In late 2008, Ballmer charged Terry Myerson with the task of getting development of the company’s mobile OS onto a path for success.

Myerson wasted little time in stuffing much of the work on Photon up to that point into the bin where it belonged, hitting the ‘reset’ button on development of Microsoft’s new OS. Given the strong competition presented by its rivals, Myerson’s decision was unquestionably the right one. But that tough call once again left Microsoft with a long delay before it could finally ship a smartphone OS that was even close to matching its strongest contenders in the mobile market.

By that time, Microsoft had already released Windows Mobile 6.1, an incremental update to WM6, but it was clear that it would be a long time until its next-gen OS was ready to roll. While work continued on that front, it was left with little choice but to ship another stopgap update to its ageing operating system.

In 2009, it released Windows Mobile 6.5 – but by that point, even Ballmer was ready to concede publicly that Microsoft’s smartphone efforts weren’t going to plan. In March of that year, a few weeks before it reached the RTM (release to manufacturers) milestone, Ballmer admitted that it was “not the full release we wanted” and said that the high-end features that buyers craved would “come on Windows Mobile 7 next year”.

Even so, he couldn’t resist a dig at Apple’s device, pointing out at the same time that Microsoft “did sell more Windows Mobile devices last year than Apple did iPhones – just an important factoid to have.” Once again exhibiting an unfortunate lack of prescience, Ballmer also took a jab at Android sales, noting that “Google was nowhere to be seen, except in Silicon Valley, I’m sure.”

Later that year, though, Ballmer was somewhat more realistic, admitting that Microsoft had “screwed up with Windows Mobile”, and promising that “this will not happen again”.

But Microsoft’s confused approach to the mobile market was muddied further by ‘Project Pink’, a calamitous effort that began in 2008 with the aim of targeting young buyers with devices that were narrowly focused on social media and ‘sharing’. Bizarrely, Pink was developed entirely separately from the Windows Mobile efforts until Microsoft senior vice president Andy Lees took control, although according to Engadget, he had very little enthusiasm for the project in the first place.

Having been delayed and extensively revised – moving from the Sidekick platform that Microsoft had acquired with its purchase of Danger, Inc., to Windows CE – Pink eventually made it to market as the two ill-fated KIN phones in May 2010, far later than originally planned, in one of the most disastrous device launches ever seen. Just seven weeks after their release, both devices were pulled from sale.

But shortly before KIN’s doomed launch, Microsoft finally gave the world a look at its long-awaited new smartphone operating system.

Windows Mobile Phone 7

On February 15, 2010, Microsoft finally unveiled its next-gen mobile OS: Windows Phone 7 Series. It was a stunning, radical departure from the company’s previous efforts, with an extraordinary focus on design and style based around the principles of its newly-christened ‘Metro’ design language. Where Photon had attempted to shoehorn in a few token elements from Media Center and Zune, Windows Phone 7 Series embraced the design philosophy of those products wholeheartedly, taking them to an entirely new level.

Clean and crisp typography was at the heart of the user interface, along with ‘flat’ blocks of color, rather than the ‘chrome’-heavy gradients and shading found on other platforms. The OS was alive with sleek transitions and animations, and a Start screen filled with Live Tiles – large colorful blocks offering an executive summary of key information at a glance without the need to dive into individual apps.

Microsoft built further on the idea of not having to constantly jump in and out of apps by developing the OS around an interface paradigm that it described as ‘Hubs’ – centralized portals in which groups of related apps could be clustered for convenience, while also surfacing key tasks and resources to the Hub level, allowing users to get things done without the need to keep opening up individual bits of software.

The People Hub, for example, included a unified contacts list from multiple sources (such as Facebook or Gmail), but also incorporated content from social networks, such as images posted by friends on Facebook. Similar unified ‘experiences’ were available in other Hubs, such as Music + Video, or Office.

Amid the enthusiastic buzz about the new OS, there was, however, a kick in the teeth for those who had purchased Windows Mobile 6.5 devices just months before Windows Phone 7 was announced. Those users, and others with even older devices, were told that there was no upgrade path for them to the new OS; they would have to buy a new handset if they wished to enjoy the company’s exciting reimagining of the mobile experience.

Nonetheless, after the long, painful wait for its arrival, Microsoft had delivered a truly impressive vision for its mobile OS that offered something genuinely distinctive from its rivals – and it seemed to have been worth the wait. In its announcement, Microsoft promised extensive support from many of the world’s largest carriers, along with manufacturer support from Dell, Garmin-Asus, HTC, HP, LG, Samsung, Sony Ericsson and Toshiba, as well as chipmaker Qualcomm.

Despite its delayed arrival, it appeared that Microsoft finally had a strong platform on which to build its efforts to take on its biggest competitors. Unfortunately, once again, the company allowed its hubris to get the better of it.

When the OS reached RTM in September 2010, Microsoft staged a mock ‘funeral’ for its iPhone and BlackBerry rivals – a dreadful stunt apparently intimating that the company had ‘buried’ the competition before its own product had even launched. Even at the time, that event was considered to be woefully misguided, but with the added benefit of hindsight, it was nothing less than excruciating.

While Windows Phone 7 (the ‘Series’ was dropped before its official launch) was undeniably stylish, its substance left much to be desired - a consequence of Microsoft's efforts to rush the product to market. Much like the original iPhone had lacked various basic features, WP7 had no support for copy-and-paste (which Microsoft declared its customers didn't need), custom ringtones, tethering, and no proper multitasking support either. Microsoft also believed that the Live Tiles on the Start screen negated the need for a notifications pane.

Such fundamental omissions were more forgivable on a breakthrough product like the first iPhone, but when Microsoft was launching its product literally years behind its rivals, the funeral stunt made the company seem arrogant and almost deluded in its apparent belief that it had already ‘got the job done’.

That perception was only exacerbated when the first batch of Windows Phone 7 devices were revealed with only half of the hardware partners that Microsoft had named in its earlier announcement. Only Dell, HTC, LG and Samsung unveiled launch devices for the new OS; ultimately, Garmin-Asus, HP and Sony Ericsson would never offer a single WP7 device between them.

The burning platform

After the buzz surrounding its launch had died down, it soon became apparent to many that Windows Phone 7 perhaps wasn’t quite as exciting as it had first appeared, and the absence of various key features was only one part of that realization. The pace at which Microsoft delivered those missing features added to the frustrations of users and potential buyers.

The first significant update, ‘NoDo’ (an inside joke – ‘No Donut’, in reference to the Android update of the same name) did not arrive until five months after WP7’s release, finally bringing copy-and-paste support, among other minor improvements, but its rollout came with a sprinkling of Microsoft's apologies for its later-than-expected arrival.

Many were disappointed too by the limited selection of apps available on the Windows Phone Marketplace. While essentials such as Facebook and Twitter were available at launch, it didn’t take long for users to realize that other third-party apps were being launched first (and in some cases, only) on iPhone and Android, as developers were wary of spending time and resources on an unproven OS with few users.

The first WP7 devices were somewhat lackluster as well. HTC’s selection of handsets was poorly differentiated, although the giant HD7, with its 4.3-inch display, proved to be a popular choice as demand for larger screens across all platforms continued to grow. In the weeks and months following its launch, Dell’s Venue Pro suffered from any number of technical issues – from SIM card problems to Wi-Fi connectivity flaws – and many of those attempting to exchange malfunctioning handsets found that the company initially had no replacement units to offer them due to supply constraints.

Windows Phone 7’s story might well have ended a good deal sooner, were it not for a well-placed ally in Finland.

In September 2010, Stephen Elop had left his position as head of Microsoft’s Business Division, where he was in charge of several major product lines including Office, to become the new CEO of Nokia. Like Microsoft, Nokia had also been caught out by the rise of iPhone and Android, and by the time of Elop’s appointment at the top of the company, it was painfully obvious to everyone that its Symbian OS was no longer fit for purpose in the new age of touch-focused smart devices. Adding to its woes, Nokia’s efforts on the Linux-based MeeGo front weren’t going quite as well as the company had hoped – when Elop joined, its first MeeGo device was still a year away.

With its own OS development efforts lagging, and Symbian no longer competitive, Nokia faced only one realistic alternative: to use a third-party OS. In February 2011, Stephen Elop sent an internal communiqué to Nokia’s staff, which quickly became known as “the burning platform memo”.

In it, Elop likened Nokia’s position to that of the protagonist in an apocryphal tale of a man on an oil platform in the midst of a rapidly unfolding disaster in the middle of the night. With the flames practically licking at his back, he faces the terrible choice of standing on the platform to be burned alive, or taking his chances and plunging dozens of meters into the dark, icy waters below. “We too, are standing on a ‘burning platform’”, Elop said, “and we must decide how we are going to change our behaviour.”

Soon afterwards, Nokia announced that it was putting all of its smartphone eggs in Microsoft’s Windows Phone 7 basket.

After a shaky start from Microsoft’s mobile OS, it was a stunning coup to win over the world’s largest handset-maker, which had manufactured around 450 million of the 1.4 billion phones shipped around the world in 2010.

The future suddenly looked very bright indeed for Windows Phone 7.

Mango

A few days later, at Mobile World Congress 2011, Microsoft announced details of its next major update in the works for the OS, which promised to finally deliver some big new features, including better multitasking support, Twitter integration into the People Hub, and a vastly improved web browsing experience with Internet Explorer 9.

In May of that year, Microsoft announced further details about what it referred to as the ‘Mango’ update, revealing even more appealing features, including enhanced Live Tiles, linked email inboxes, and a big upgrade for Bing searches, incorporating new ‘Local Scout’ functionality, “providing hyper-local search results for information on shopping, restaurants and activities”.

Microsoft was also pleased - and probably a bit relieved - to reveal that it had signed up new partners to the platform. Acer and ZTE were among them, and for a second time, Microsoft announced that Toshiba would build a Windows Phone device. Indeed, that handset was finally unveiled in July 2011, as the stylish Fujitsu-Toshiba IS12T - which, to this day, is still in an extremely exclusive club of water- and dust-resistant Windows Phones.

Significantly, Mango would be the version of the OS that would ship on Nokia’s first Windows Phone handsets, and there were high expectations for what the two companies would bring to market together. When the partnership was first announced, Elop had emphasized that Nokia would have a special relationship with Microsoft, allowing it “to jointly drive the future of Windows Phone 7”. Nokia, he said, would “have the ability to do customizations and extensions to the software environment that are unique and therefore differentiate”, emphasizing that it was “not a standard OEM agreement”.

When the first Nokia Windows Phones – the Lumia 800 and Lumia 710 – were unveiled by Elop in October 2011, he declared that “Lumia is the first real Windows Phone”, something of a middle-finger to the other companies that had been working on the platform since long before Nokia joined the party.

While the Lumia 710 was a pretty humdrum low-cost device, the Lumia 800 was the real star of the show. The bold, beautiful colours, extraordinarily stylish polycarbonate bodywork, and curved glass display all combined to make the device stand out among the comparatively ordinary-looking handsets that had been revealed with Windows Phone up until that point - albeit with the exception of the psychedelic Fujitsu-Toshiba IS12T, although its availability was officially limited only to Japan.

Nonetheless, there was no missing the fact that the Lumia 800 wasn’t uniquely designed for Windows Phone; it was a light modification of the Nokia N9, the company’s one and only MeeGo handset, which – confusingly – it had launched a few months earlier, despite having already signalled that its commitment to MeeGo was effectively dead.

As anticipated, the Lumia 800 and 710 soon went on sale with the Mango update – by then known as Windows Phone 7.5 – pre-installed. But while some had expected Nokia to make sweeping changes to the OS, in fact, it had left Windows Phone 7.5 more or less intact, swapping out some Microsoft services for its own, and making a few additional firmware revisions to better integrate its own hardware with the OS.

While both devices attracted a great deal of attention at launch, not everyone was entirely convinced that they would succeed. As with the first generation of Windows Phones, there were concerns that Nokia’s Lumia handsets were priced too highly. A senior executive at European mobile giant Telefónica said in no uncertain terms that the Lumia 800 was simply “too expensive” and suggested that the device “doesn’t differentiate sufficiently”.

Nonetheless, Nokia was convinced that it had succeeded in developing the right product and price mix with both the 800 and 710, and just a few weeks later, the company was ready to unveil a third Windows Phone.

In January 2012, it unveiled a new flagship for its Windows Phone range, the Lumia 900, which built on the design language of the Lumia 800, offering various improvements over that device, including a larger display and more storage, along with the introduction of a front-facing camera – an omission on all first-generation Windows Phones, as well as the first Lumias.

Perhaps inspired by the misguided complacency of Ballmer and Microsoft in earlier years, Nokia decided to abandon any sense of humility with its Lumia 900 launch. Instead, it decided that being a pompous blowhard was the best approach; in April 2012, the company declared: “The smartphone beta test is over” – implying that all other devices from each manufacturer on every other platform had somehow just been a dry run leading up to Nokia’s release of the ultimate smartphone.

Nokia was quickly forced to eat those poorly chosen words, as customers soon complained of issues including a purple hue on the display, network connectivity issues, faulty hardware buttons, and various other problems, documented by Windows [Phone] Central. Some of these flaws were resolved with software patches, but the company was left looking a little foolish having raised expectations to such great heights with its ‘beta test’ proclamation.

But the complaints that it faced over those issues were nothing compared with the anger and frustration of Lumia 900 buyers just a few weeks later.

Apollo

In the dying days of the ill-fated Photon project, before the ‘reset’ button was pressed, Microsoft was quietly working on efforts to make the Windows NT kernel run on ARM processor architecture commonly used on mobile devices such as smartphones and tablets. By the time the company had refocused its mobile development onto what would eventually be launched as Windows Phone 7, the NT-on-ARM efforts had matured considerably, and even as development continued on WP7, engineers were already working on building a new version of Windows Phone on the NT kernel.

Development of this new version, codenamed ‘Apollo’, was closely integrated with teams working on Windows 8 and Windows RT, and Microsoft was understandably enthusiastic about the prospects of being able to maintain multiple operating systems based on just one kernel. By ditching the Windows CE architecture for Windows Phone, it also had a much more convincing proposition for developers, who would be able to create apps that could be ported more easily between smartphones, tablets and PCs.

In June 2012, just a couple of days after it had unveiled its first-generation Surface [Pro] and Surface RT tablets (running Windows 8 Pro and RT, respectively), Microsoft was finally ready to share Apollo with the world for the first time. At an event in San Francisco, it unveiled Windows Phone 8, and while the visual similarities with its predecessor were obvious, it delivered an astonishing array of changes and improvements compared with earlier versions. For all intents and purposes, Apollo was a new operating system, which just happened to look like what had come before. Symbolic of this change – and mirroring a similar move for Windows 8 and RT – Windows Phone 8 ditched the old Windows ‘flag’ logo in favor of the new, sharper, monochromatic trapezoid version.

The list of changes and additions was seemingly endless: over-the-air updates, true multitasking support, a new and more flexible Start screen layout, NFC, Internet Explorer 10, support for high-definition displays and multi-core CPUs, microSD card support, Bitlocker encryption, and the ability to capture screenshots (!) were just some of the major additions, while thousands of smaller tweaks and improvements had been made across the entire OS. Suddenly, it felt like Microsoft was finally catching up with its smartphone rivals.

However, along with all the big announcements, there was devastating news for those who had purchased Windows Phone 7.x devices. Just a year and a half after the first Windows Phone 7 handsets had gone on sale, and just two months after the flagship Lumia 900 reached stores with Windows Phone 7.5, Microsoft announced that no existing handsets would be able to upgrade to Windows Phone 8.

Needless to say, those who had recently signed a two-year-contract on AT&T to get the Lumia 900 felt particularly hard done by, quickly venting their frustrations at both Nokia and Microsoft.

Microsoft promised owners of these older devices that they would not be abandoned, and said that Windows Phone 7.x handsets would be eligible for a further update, Windows Phone 7.8, bringing a handful of new features, such as the updated Start screen from Windows Phone 8. Unfortunately, carrier and manufacturer support for Windows Phone 7.8 was poor, to say the least, as Microsoft’s partners saw little point in spending time and resources on updating devices that were effectively heading for a dead end anyway.

Microsoft also said that it would introduce an early access program for enthusiasts and developers to install previews of new versions of the OS before they were generally available, although it didn’t give any indication of how long it would take for those plans to be implemented.

Microsoft brought Windows Phone 8 to market in late 2012 – but just as with its Windows Phone 7 launch, it did so with minimal support from its hardware partners. By that point, LG had followed Dell in abandoning the platform completely, and Acer, Toshiba and ZTE were nowhere to be seen either, leaving only HTC, Nokia and Samsung to offer Windows Phone 8 hardware at its launch.

Microsoft brought Windows Phone 8 to market in late 2012 – but just as with its Windows Phone 7 launch, it did so with minimal support from its hardware partners. By that point, LG had followed Dell in abandoning the platform completely, and Acer, Toshiba and ZTE were nowhere to be seen either, leaving only HTC, Nokia and Samsung to offer Windows Phone 8 hardware at its launch.

Even so, the launch line-up for Windows Phone 8 was much more convincing than that of WP7. Alongside the relatively ordinary Lumia 820, Nokia also unveiled the remarkable Lumia 920 flagship, but some potential buyers were frustrated by the lack of a low-cost Nokia device at launch.

Unusually – and perhaps in an effort to dissuade growing concerns that Nokia would dominate the Windows Phone hardware ecosystem, leaving little room for other OEMs to succeed – Microsoft focused heavily on HTC, referring to it as the manufacturer of the new operating system’s ‘signature devices’. Indeed, HTC’s launch handsets were (slightly awkwardly) named directly after the OS itself: the Windows Phone 8X and Windows Phone 8S.

Unusually – and perhaps in an effort to dissuade growing concerns that Nokia would dominate the Windows Phone hardware ecosystem, leaving little room for other OEMs to succeed – Microsoft focused heavily on HTC, referring to it as the manufacturer of the new operating system’s ‘signature devices’. Indeed, HTC’s launch handsets were (slightly awkwardly) named directly after the OS itself: the Windows Phone 8X and Windows Phone 8S.

Of course, a wider range of devices was introduced in the months that followed, including the Lumia 520, which became the single most popular Windows device to date, and is still the most widely used Windows Phone in the world.

Nokia also launched the remarkable Lumia 1020, cramming the magnificent 41-megapixel camera from its Symbian-based 808 PureView into the Windows Phone handset. Indeed, Nokia's range was growing into an incredibly diverse selection of devices - but as its range expanded, it also became increasingly confusing, with little real differentiation between many of its smartphones.

Microsoft’s development of the OS ended up mirroring that of WP7 in its pace; the company released its first incremental update – General Distribution Release 1, or GDR1 – just a few weeks after the first devices went on sale, but its next more substantial update didn’t arrive until seven months later. GDR2 was also a relatively modest update, delivering some handy new features and improvements, but GDR3 – which was announced in October 2013, and also known as 'Windows Phone 8 Update 3' – was where the OS picked up some much more significant changes.

For Windows Phone enthusiasts, the most exciting new feature was the long-awaited launch of the Preview for Developers Program. Over a year after the program was first announced, Microsoft released an early version of GDR3 to registered developers (although in practice, anyone could register fairly easily and at no cost).

Among various other additions, it introduced support for Full HD (1080p) displays and Qualcomm’s Snapdragon 800 SoC for the first time, paving the way for ‘true’ flagships that could compete more effectively with the powerful devices being offered on rival platforms. The 6-inch Lumia 1520 and 5-inch Lumia Icon flagships were among the first to launch with GDR3, and like other Windows Phone 8 updates, it was made available over-the-air to other WP8 devices, bringing features such as a screen rotation lock and custom notification sounds. The fact that it took three years after WP7 first launched for such basic features to reach Windows Phones was emblematic of the nature of the operating system’s development; a common criticism against the OS was that it had constantly been playing ‘catch-up’ with its rivals.

But after spending so many years being left behind, Microsoft was keen to finally level the playing field – and to take the fight to its rivals in a more aggressive and confident way than ever before.

Blue

Even before Windows 8 – the PC operating system – had launched, there were rumors of an update on the way codenamed ‘Blue’. By November 2012, just weeks after the OS had launched, it was becoming clear that Blue would be a major Service Pack-style update, delivering a substantial overhaul to the desktop OS, including significant UI changes. Behind the scenes, Microsoft was also rumored to be revising its pricing structure for the OS.

In May 2013, Microsoft confirmed that Blue would be delivered to PCs before the end of year as the free Windows 8.1 update, but just a few weeks later, details emerged revealing that the Windows Phone version of Blue would not arrive until sometime in 2014. While Microsoft had originally intended for its updates to Windows Phone 8 to roll out at a much more accelerated pace, The Verge reported that problems in the update approval process – particularly with regard to unlocked devices, and how they connected to carrier networks – had set things back considerably.

After GDRs 1-3 made their way to WP8 devices in 2013, Blue was officially unveiled as Windows Phone 8.1 at Microsoft’s Build conference in April 2014.

The update expanded the platform's hardware support considerably; after GDR3 had introduced support for the high-end Snapdragon 800 SoC, Windows Phone 8.1 added the Snapdragon 200 and 400 to the list too, paving the way for increasingly capable handsets at lower price points.

As with Windows Phone 8, Microsoft had made a considerable effort to introduce a wide range of new features. Windows Phone 8.1 finally delivered a notification center to the OS – known as the Action Center – along with an overhauled app store, multitasking improvements, new lockscreen features, deeper Skype integration, a structured file system, and many other additions. Significantly, the new version of the OS also offered big improvements for business and enterprise customers, including VPN support, encrypted email, and enhanced MDM policies for corporate buyers, finally equipping Windows Phone with key features needed to make devices more suitable for use in business environments.

Microsoft reworked the keyboard too, which was already considered to be a pretty decent offering in previous versions of the OS. The Word Flow keyboard included Swype-style functionality, allowing users to swipe their thumb across the display from letter to letter, spelling out each word with a single gesture. Such was the impressive performance of the keyboard that it was used to break the Guinness World Record for world’s fastest typing on a touchscreen (although that record was later broken again on an Android device).

But one of the most greatly anticipated new features in Windows Phone 8.1 was one that had originally been rumored as far back as September 2013: Cortana, its digital ‘personal assistant’. While relatively limited in functionality at first – and initially restricted only to the United States – Microsoft continued to build on Cortana's foundations, massively expanding the capabilities of the assistant on Windows devices.

Aside from the rumors, though, September 2013 was an important month for Windows Phone for a very different reason. By that point, it had become painfully clear that Windows Phone had not been the commercial success that some had predicted it would be. Having focused all of its smartphone efforts on Windows Phone, Lumia sales were pitifully small and failing to grow at any meaningful rate. By 2013, Nokia was already planning to launch low-cost handsets running a forked version of Android, and Microsoft could evidently see trouble brewing.

Nokia's own product mix wasn't doing it any favors either. It was spending huge sums on designing, building and marketing ever more devices - even to the point that it launched its own Windows RT tablet, the Lumia 2520 - in late 2013. Costs were rapidly increasing, while sales weren't growing quickly enough to offset them.

_full.jpg)

With Nokia shareholders becoming restless over the lack of success from its Windows-based strategy, and with Nokia already preparing to release its first Android devices, speculation began to grow that the Finnish company might eventually ditch Windows Phone in favor of nurturing its Android experiment into a larger, more complete range of devices. Given that Lumia had come to overwhelmingly dominate Windows Phone sales by that point, Nokia’s departure from the platform would have dealt a severe blow to Microsoft’s mobile ambitions. Against this backdrop, on September 3, 2013, Microsoft announced that it was acquiring Nokia’s devices and services business in a deal worth around $7.2 billion.

The deal was finally completed on April 25, 2014 – three weeks after Windows Phone 8.1 was unveiled (and two months after Nokia – locked into commitments with suppliers, retailers and other partners, had launched its dismal ‘Nokia X family’ of Android handsets; the less said about those, the better). Microsoft boldly – perhaps bravely – announced that its acquisition ‘aimed to remake the mobile market’.

But in fact, Microsoft had made another important change just weeks before its Nokia acquisition was completed, which aimed to remake, and reinvigorate, its own mobile platform. Crucially, it also hoped that that change would reduce its own burden for building devices, in the knowledge that it was about to become the single largest handset-maker in its ecosystem by a massive margin.

Indeed, that change – introduced as part of its Windows Phone 8.1 announcement – was not a new feature, or a tweak or improvement to an existing one. As the rumors had suggested way back in November 2012, Microsoft introduced a fundamental overhaul of its Windows licensing fees, making the OS free for smartphones and other devices with screens smaller than 9-inches.

In 2012, an executive from ZTE – which, at the time, was a Windows Phone partner – revealed that the company paid around $23-$31 to Microsoft to license the OS for each device. For flagship-class handsets retailing for hundreds of dollars, that might seem like a trivial amount – but for manufacturers aiming to build low-cost smartphones, that expense was cost-prohibitive, and created an insurmountable barrier preventing many OEMs from joining Microsoft’s mobile platform. By dropping those fees, Microsoft opened the floodgates to a wave of new partners ready to embrace Windows on both phones and small, affordable tablets.

By October 2014, just six months after announcing the end of Windows licensing fees on these devices, Microsoft had attracted 50 new hardware partners, many of which were offering Windows Phones as well as tablets, and even small, low-cost laptops. Even more companies continued to join the Windows platform in the months that followed.

Nonetheless, even after its deal with Nokia was finalized, Microsoft continued to flood the market with new Lumia handsets, and its range became increasingly confusing with significant overlap between many of its devices.

In November 2014, it unveiled the Lumia 535, the first Windows Phone to carry its own brand, rather than that of Nokia (which had only licensed its brand to Microsoft for a limited time). Along with the 535, Microsoft launched a further six lower-end handsets - Lumias 430, 435, 532, 540, 640 and 640 XL - in just six months, while its mid-range and high-end offerings stagnated. Almost eighteen months passed without Microsoft announcing a new flagship (and until last October, its most recent top-tier device, the Lumia 930 - which went on sale in mid-2014 - was just an international variant of the Verizon-only Lumia Icon that had been released several months before it).

But despite its hopes of growing the platform with new partner devices, alongside its own masses of handsets, Microsoft’s efforts ultimately failed.

Although dozens of new manufacturers launched Windows Phones, the latest figures – published a few weeks ago by AdDuplex – indicate that Nokia and Microsoft Lumia devices still make up a staggering 97% of active Windows phones. To make matters worse, sales of Lumia devices are no longer growing, but falling at an alarming rate; Microsoft’s latest quarterly report showed that Lumia sales had plummeted by 57% year-over-year.

Windows Phone’s global smartphone market share now stands at less than 2%.

Soon

In July 2014, less than three months after completing its Nokia acquisition, Microsoft announced the biggest job cuts in its history, laying off 18,000 people, with over two-thirds of those having just joined the company from Nokia. A year later, amid a massive $7.6 billion write-down – an ‘impairment charge’ associated with its purchase of Nokia's hardware business – the company revealed that it was restructuring its phone division, and cutting a further 7,800 jobs from its workforce.

Microsoft’s CEO, Satya Nadella, said that the company was “moving from a strategy to grow a standalone phone business to a strategy to grow and create a vibrant Windows ecosystem including our first-party device family”. If that sounds familiar, that’s because it was much the same strategy that Microsoft had been trying to pull off since it removed its Windows licensing fees for phones – the difference this time around was that Microsoft itself was signalling a dramatic scaling back of its own hardware portfolio, actively offloading far more of the responsibility for building devices to its partners.

Today, the company continues to sell the Lumia handsets that it launched with Windows Phone 8.1, and it has since unveiled its newest portfolio of devices running Windows 10 Mobile. Nadella said last year that Microsoft would build new handsets focusing on just three key areas: value phones, business phones and flagships.

Last October, it unveiled the Lumia 550 as its low-cost entry-level device, alongside the high-end Lumia 950 and 950 XL. Yesterday, it announced the Lumia 650 with little fanfare as its new business-focused handset - although aside from its sleek metal body, there’s very little evidence of what supposedly makes that device uniquely suited to business users.

Meanwhile, Windows 10 Mobile itself hasn’t had the smoothest of launches. While diehard Windows fans are predictably gushing with praise for it, you don’t have to search for long across the web and social media to find an extensive list of complaints about the new OS - even on Microsoft’s costly flagships - with problems ranging from random device crashes and reboots, to buggy software, unimpressive battery life, and other reliability issues.

And development delays – a recurring theme throughout the history of the platform since the days of Photon – remain an issue too. Microsoft originally planned to begin upgrading some of its Windows Phone 8.1 handsets back in December, but then pushed its plans back to ‘early next year’. Many of its carrier partners were clearly left with the impression that it would roll out the update in January, but rumors of a further delay until at least February proved to be true, and the company still hasn’t announced any details of exactly when devices will be upgraded.

But despite reports of its imminent demise, Microsoft’s mobile efforts aren’t dead yet, although it’s not hard to understand why people have been left with that impression.

Microsoft, the biggest vendor of Windows phones, is reducing the number of handsets it produces, at a time when the platform’s market share is already lower than anyone envisaged amid the enthusiasm and excitement when Windows Phone 7 was first unveiled. And even while sales of its own Lumia devices have been falling, those of its dozens of new Windows Phone partners haven’t been rising enough to make up the difference. Viewed in this simple, raw context, it’s hard to see Microsoft’s slice of the global smartphone market getting bigger.

Even so, there are still signs of life.

The Universal Windows Platform – which allows developers to create apps that run across phones, tablets, PCs and many other types of device with only minimal changes – is a hugely important asset for Windows 10 Mobile’s future prospects. Many big brands have already launched Universal apps for Windows 10 PCs and phones in recent months, and many more have signalled plans to do so. Even so, not everyone is convinced.

Some companies aren’t yet sold on the Universal vision, and have chosen to focus their development on ‘classic’ Win32 desktop applications instead. In a recent high-profile embarrassment, one of Microsoft’s Windows 10 launch partners binned its Universal app development efforts. Tencent – the Chinese multimedia giant that Microsoft named in its Windows 10 launch announcement – said that it was ending work on its Universal app for QQ, the company’s IM platform with over 800 million users, specifically citing the falling market share of Windows phones as its reason for doing so, and saying that it had seen little evidence that Microsoft was doing enough to reverse that decline.

Microsoft’s ‘app-gap’ problem – which the company famously declared it had 'closed' back in 2013 – has been another consistent issue since WP7’s launch, and the continuing drop in market share will hardly offer much incentive for developers to bring their apps across. But of course, the beauty of the Universal Windows Platform is that apps run across multiple device types – software-makers don’t need to develop uniquely for Windows phones, when they can also create apps for the 200 million other devices that are already running Windows 10, a number that Microsoft expects to quickly grow to over one billion.

Whether or not that will convince developers to create software that can run across phones too remains to be seen, even with compelling tools such as Microsoft’s ‘Project Islandwood’, designed to make it easy to port an iOS app to Windows 10 with relatively little effort.

However, at the same time, Microsoft hasn't been making it easy to love Windows phones, as it ports more of its own software across to other platforms, including features previously unique to its own OS, such as Office, Cortana and the Word Flow keyboard.

But even while tales of woe and demise follow almost any mention of Windows on phones these days, manufacturers are already investing in developing new devices for Windows 10 Mobile – from low-cost phones to stylish and well-featured flagship-class handsets, and even small tablets. Even HP, which bailed on Windows Phone 7 before the OS officially launched, appears to be preparing a Windows 10 Mobile handset, the Elite x3.

And Microsoft itself hasn’t given up on mobile hardware. While its new-generation portfolio of handsets is somewhat lackluster, the company is believed to be working on a new class of mobile device, starting with the mythical 'Surface phone', building on the exciting foundations laid down in Windows 10 Mobile.

Existing flagships running the new OS include support for its PC-like Continuum feature, which allows users to connect a mouse and keyboard to the handset, and then connect the handset to a larger display – effectively turning the phone into a mini-PC, including a desktop-style UI and Start menu. Microsoft's next-gen device could take this setup to a whole new level.

It’s not hard to imagine a 'mobile-first' future in which such devices become the norm, and as mobile hardware becomes ever more powerful, Microsoft may well position itself at the forefront of a new era in which users can own a single device – for communicating, for productivity and for gaming – in their pockets or handbags, which can be used on the go, or hooked up to a big screen.

And if the company can build on its successful Surface tablet model – by creating desirable ‘pocket PC’ handsets that prove the commercial viability of its distinctive new hardware – it may even succeed in encouraging its hardware partners to take on the lion’s share of device-building, allowing it to maintain a smaller ‘Nexus-style’ hardware business that may even lead the mobile market in new and exciting directions, after years of lagging behind its rivals.

That's a wildly optimistic vision, to be sure, but Microsoft has established some strong foundations on which to build its latest mobile efforts. Even so, there is still a great deal of uncertainty surrounding them - and of course, there was no shortage of optimism surrounding Microsoft's future in the mobile space when Windows Phone 7 was first unveiled all those years ago, brimming with potential waiting to be realized.

In many ways, perhaps, that’s always been the problem with Windows phones – the waiting never ends; the good stuff is always coming soon.

Additional image credits: Photon screenshots via XDA Developers

25 Comments - Add comment