In recent weeks, there's been no end of coverage about the WannaCry ransomware attack - no surprise, given that it affected systems in dozens of countries around the world, as well as causing chaos for large parts of the UK's National Health Service. Earlier this month, details emerged of another major cyberthreat, known as 'Fireball', via a threat analysis report published by the noted Check Point security center.

Check Point analysts described Fireball as a "high volume Chinese threat operation which has infected over 250 million computers worldwide, and 20% of corporate networks" - a deeply concerning claim. But Microsoft said today that it has been monitoring this threat since 2015, and that "while the threat is real, the reported magnitude of its reach might have been overblown".

Both Microsoft and Check Point agree on the delivery mechanism used by the Fireball suite to infect systems. Check Point explained:

Fireball acts as a browser-hijacker and can be turned into a full-functioning malware downloader. Fireball is capable of executing any code on the victim machines, resulting in a wide range of actions from stealing credentials to dropping additional malware.

Fireball is spread mostly via bundling i.e. installed on victim machines alongside a wanted program, often without the user’s consent.

Microsoft added:

In almost three years of tracking this group of threats and the additional malware they install, we have observed that its components are designed to either persist on an infected machine, monetize via advertising, or hijack browser search and home page settings.

The most prevalent families in the Fireball suite are BrowserModifier:Win32/SupTab and BrowserModifier:Win32/Sasquor.

However, the two organizations differ in their assessment of Fireball's actual impact, and the number of machines that it successfully infected.

Check Point said that its analysis had found that over 10% of all computers in India, for example, had been infected, with a staggering 43% of corporate networks in India also affected by the malware. In Indonesia, the corporate network infection rate was said to be even higher, at a whopping 60%, and even in the US, almost 11% was said to be infected. The image below shows Fireball global infection rates according to Check Point (with darker shades indicating more infections):

The image below shows Microsoft's interpretation of the infection rate based on its analysis and detection since 2015:

While there are some similarities between the two images, there are some notable differences as well. Microsoft's analysis shows that the United States, for example, carried a far lower infection rate than Check Point indicates. Microsoft's data also indicates that many nations in Latin America and Africa have lower infection rates than Check Point's map suggests.

Microsoft said that there is an important distinction to be made "between estimated visits and infections", explaining:

In their report, Check Point estimated the size of the Fireball malware based on the number of visits to the search pages, and not through collection of endpoint device data. However, using this technique of site visits to estimate the volume of infected machines can be tricky:

- Not every machine that visits one of these sites is infected with malware. The search pages earn revenue regardless of how a user arrives at the page. Some may be loaded by users who are not infected during normal web browsing, for example, via advertisements or domain parking.

- The estimates were made from analyzing Alexa ranking data, which are estimates of visitor numbers based on a small percentage of Internet users. Alexa’s estimates are based on normal web browsing. They are not the kind of traffic produced by malware infections, like the Fireball threats, which only target Google Chrome and Mozilla Firefox. The Alexa traffic estimates for the Fireball domains, for example, differ from Alexa competitor SimilarWeb.

Microsoft added that it has "reached out to Check Point and requested to take a closer look at their data."

Microsoft's Hamish O'Dea, from the Windows Defender Research team, also published a breakdown of how the company believes the Fireball malware actually spread, based on "intelligence gathered from 300 million Windows Defender [antivirus] clients since 2015, plus monthly scans by the Microsoft Malicious Software Removal Tool (MSRT) on over 500 million machines since October 2016":

The table above shows the rate of monthly infections that Microsoft detected for BrowserModifier:Win32/SupTab. O'Dea said that "the spike in October 2016 reflects when we added the SupTab family to the MSRT".

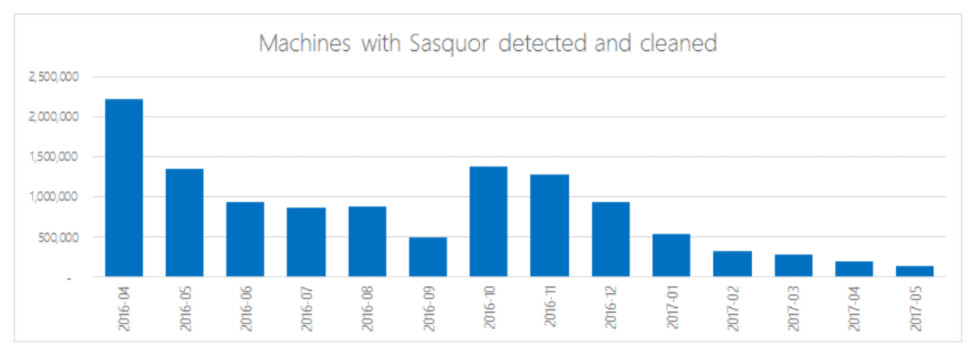

Below is a similar table for the Sasquor family of the Fireball suite. O'Dea noted that the spike in October 2016, when Sasquor was also added to the MSRT, was less significant, as that family had not been distributed for as long as SupTab before Microsoft began to remove it through its malware removal tool.

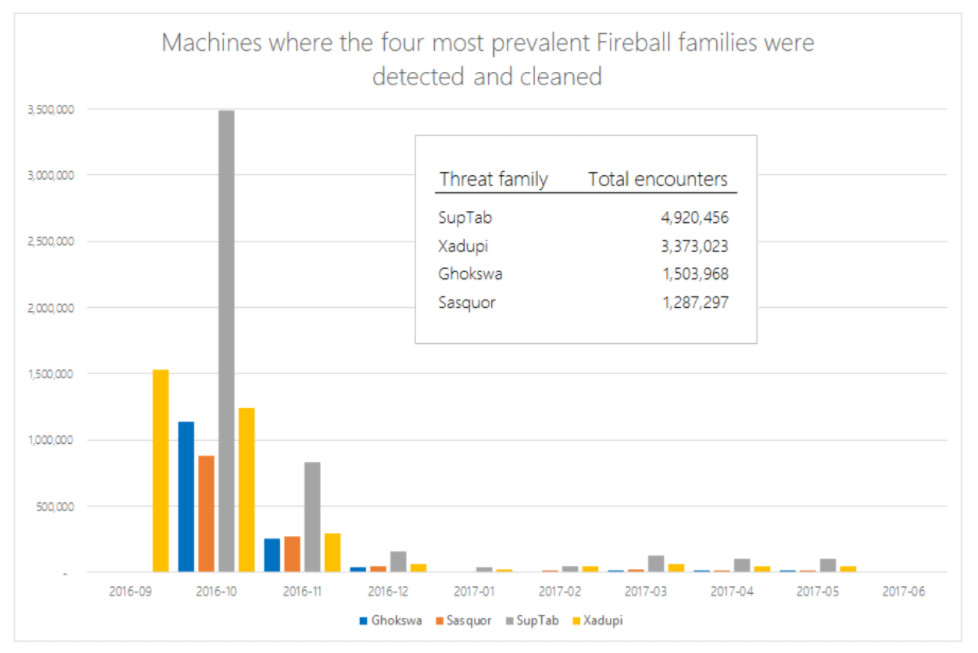

Microsoft said that all of the Fireball malware families were added to the MSRT in three waves, in September and October 2016, and February 2017. Based on its data of actual infections detected and cleaned, rather than estimates, Microsoft believes that the overall infection rate was far lower than had previously been indicated; the chart below shows the number of infections over time for the top four Fireball families:

O'Dea emphasized that the Microsoft Edge browser in Windows 10 "is not affected by the browser hijacking techniques used by Fireball", and also pointed out that the new Windows 10 S edition is not vulnerable to this threat, and other similar ones, as it is restricted to working exclusively with software downloaded from the Windows Store.

Other browsers, and other versions of the OS, are still susceptible to the Fireball threat, to varying degrees. Microsoft said that it will "continue to monitor and provide protection against them" through tools such as the MSRT and Windows Defender Antivirus.